What are your top resources, processes, advice, or things to avoid regarding how to think in bullets instead of long-form writing? How did you learn? What was the toughest part? What is the most useful part of using an outliner?

PS: I think this post will help many curious users understand why they shouldn’t recommend adding features to Logseq from long-form editors.

1 Like

Hello,

I’m a bit embarrassed to answer your post because I never felt like using bullet was something special or a skill to learn. That’s natural for me. Before using logseq, I used various tools (wiki like) and tried both logseq and obsidian at the same time (for evaluation). One of the many reasons I choose logseq over obsidian was because logseq had bullet and that’s how I think a document.

So I never learnt to use bullets. There was no toughest part… When I use a tool that doesn’t have bullet (or that are basic bullets) I tried to conform to the tool.

Basically the only basic concept I use is :

- If an idea is related to another (precision, description) I put it as a sub bullet

- If not I put it on the same level

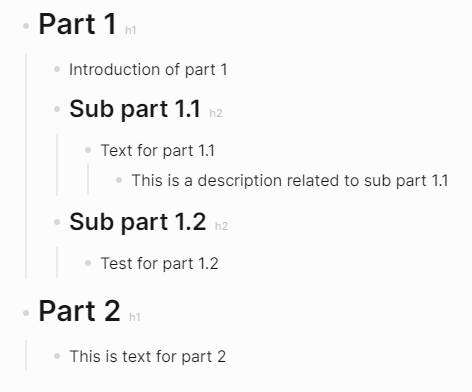

Example:

A classical document:

Introduction

# Part 1

Introduction of part 1

## Sub part 1.1

Text for part 1.1 (This is a description related to sub part 1.1)

## Sub part 1.2

Test for part 1.2

# Part 2

This is text for part 2

And here is how I would write it in logseq:

- Introduction

- # Part 1

- Introduction of part 1

- ## Sub part 1.1

- Text for part 1.1

- This is a description related to sub part 1.1

- ## Sub part 1.2

- Test for part 1.2

- # Part 2

- This is text for part 2

And it would endup in logseq as:

Note that each part is foldable and you can reduce it like:

And for the PS, I don’t understand what you mean by “long-form editors” ?

2 Likes

@gissehel thanks, I agree that there’s a natural approach to bullets, maybe at times more natural than grammar rules, and the example you post is somewhat a straightforward hierarchical problem. However, I think that there are times it is not that easy.

Ideas and thoughts happen randomly and in tandem; to organize those ideas in bullets making inferences depends on prepositions, and designing an experiment depends on hypotheses and observations, then the conclusions.

Sharing an idea so others can understand and contribute requires thinking of others; for example, if a bullet will be shared with a team, you must use complete sentences, thus the bullet has a meaning on its own.

Have you tried to decompose complex documents into bullets? For instance, legal, scientific, or technical documents.

That exercise is sometimes challenging because you need to prune the key arguments and find how those arguments relate to other parts of the text.

I like bullets because they are movable without breaking the idea. When I edit a paragraph, it is easy to create nonsense if you extract text from it.

For summarization one method I like is the Progressive Summarization by Tiago Forte; another very popular one is the Zettelkasten.

The bullet styles to write a book are very different from those you use for TODO lists; for TODOs it may make sense to follow GTD rules, focusing on action verbs.

The first post I wrote here, when I didn’t know what an outliner was Memex merge between two knowledge domains was responded by @mentaloid. I was impressed on how well he expressed his ideas using bullets, he answered my post and at the same time show me the advantages of using bullets and tought me how to use them.

I immediately got hooked into Logseq.

- If we can explain the advantages in a simple way maybe

- more people will get in love with Logseq.

- refrain from suggesting long-form features into Logseq

- which is asked too often

- understand that Logseq sees things different

- understand why

- blocks are the minimal unit

- logseq force bullets.

- which is good for them

- give it a fair try.

- stop comparing to Notion, Obsidian, etc

- in summary

- i do not think bullets are natural for everyone.

- need to be tought

- and need some practice to became skillful.

- but there should be some good advises

- to make the learning curve softer.

- show the advantages quickly

1 Like

With respect to @mentaloid , the bullet is not the basic unit, the block is the basic unit, and just happens to be represented by a bullet. The distinction is that blocks can be as long as you want or need to express the thought. If you find it clumsy when using the thought later, it’s pretty easy to break it up into sub-bullets or new pages.

Bullet Point Magnum Opus!